Regional Wall Motion Abnormalities (RWMA) in Echocardiography

A clear approach to the 17 segments, coronary patterns, and common interpretation traps

Regional wall motion abnormalities are often the first echocardiographic clue that something is wrong, sometimes before bloodwork results return and before EKG changes emerge.

Failure to identify them can result in missed critical pathology.

Recognize them and you shape downstream clinical decisions, even though echocardiography can’t see the arteries themselves.

This level of interpretation separates robotic image acquisition from the art of echocardiography

This lesson shows you how experienced sonographers evaluate left ventricular wall segments and motion patterns to recognize subtle abnormalities, avoid common pitfalls, and apply the same pattern-based thinking at the bedside.

What Wall Motion Actually Represents

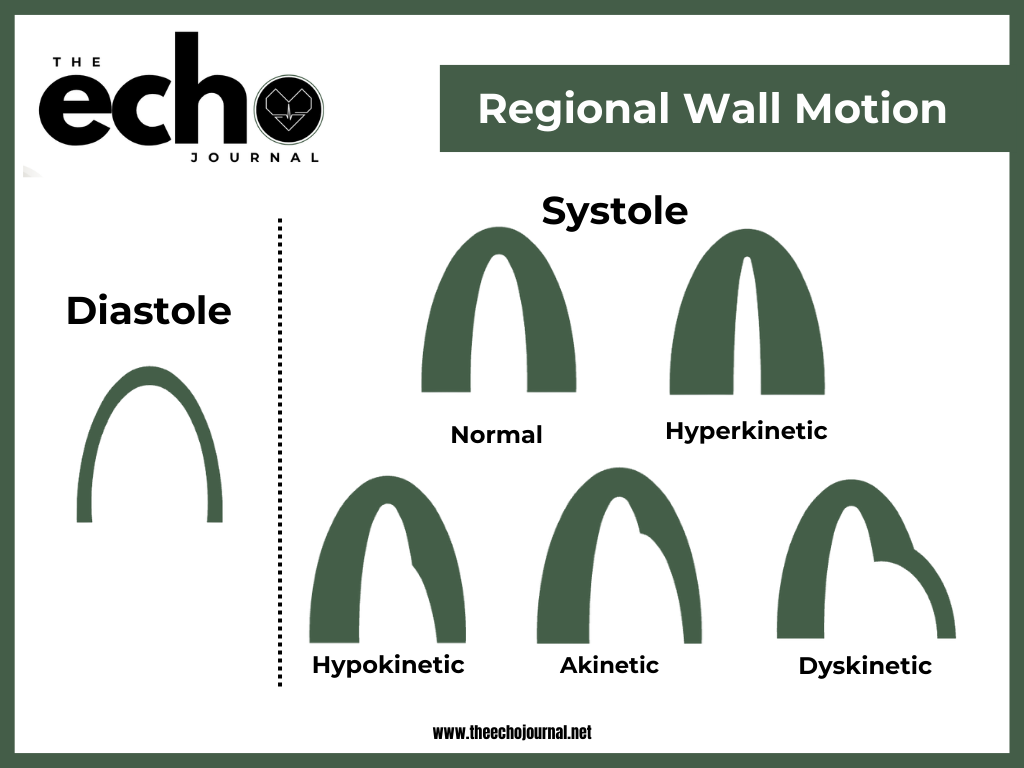

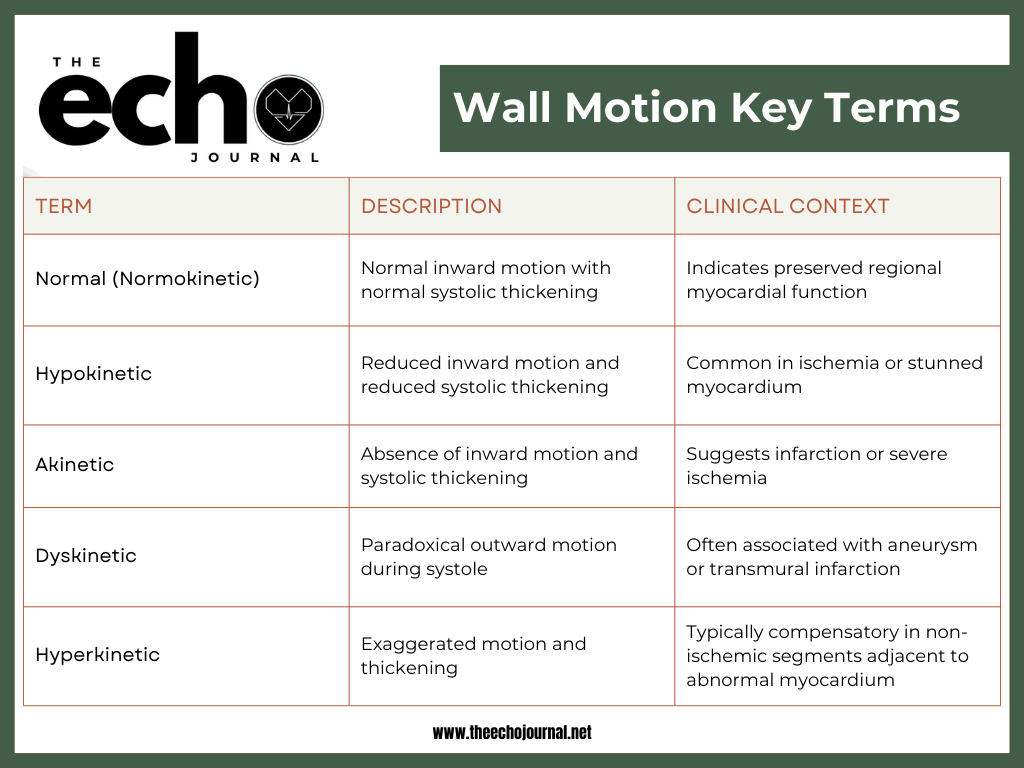

Left ventricular wall motion reflects the mechanical response of the myocardium during systole. While often discussed as a single concept, wall motion assessment is based on several underlying components that experienced sonographers evaluate together.

Left ventricular wall motion reflects:

Coordinated myocardial fiber shortening

Systolic wall thickening

Timely inward excursion toward the center of the ventricle

These components are related but not identical. A segment may appear to move yet fail to thicken appropriately, particularly in ischemia where subendocardial fibers are affected first.

Because echocardiography evaluates mechanical function rather than coronary anatomy, wall motion abnormalities represent the consequence of impaired perfusion (oxygen & nutrients reaching the heart muscle) or injury without directly visualizing arterial disease.

Fun fact: Echocardiography shows the effect of ischemia on the myocardium, while cardiac catheterization identifies the exact location of coronary artery occlusion—the gold standard for defining coronary blockages.

While definitions provide a foundation, wall motion interpretation is ultimately a visual skill developed over time. Study how these patterns vary across the cases below to learn how to differentiate each type of motion.

ASE guidelines recommend assessing regional wall motion abnormalities in at least two orthogonal views using 2D imaging, with ultrasound-enhancing agents applied according to site-specific protocols when needed.

Optimizing image quality often requires adjusting patient breathing (small, medium, or deep inspiration) and positioning to minimize lung artifact and obtain true on-axis views for accurate interpretation.

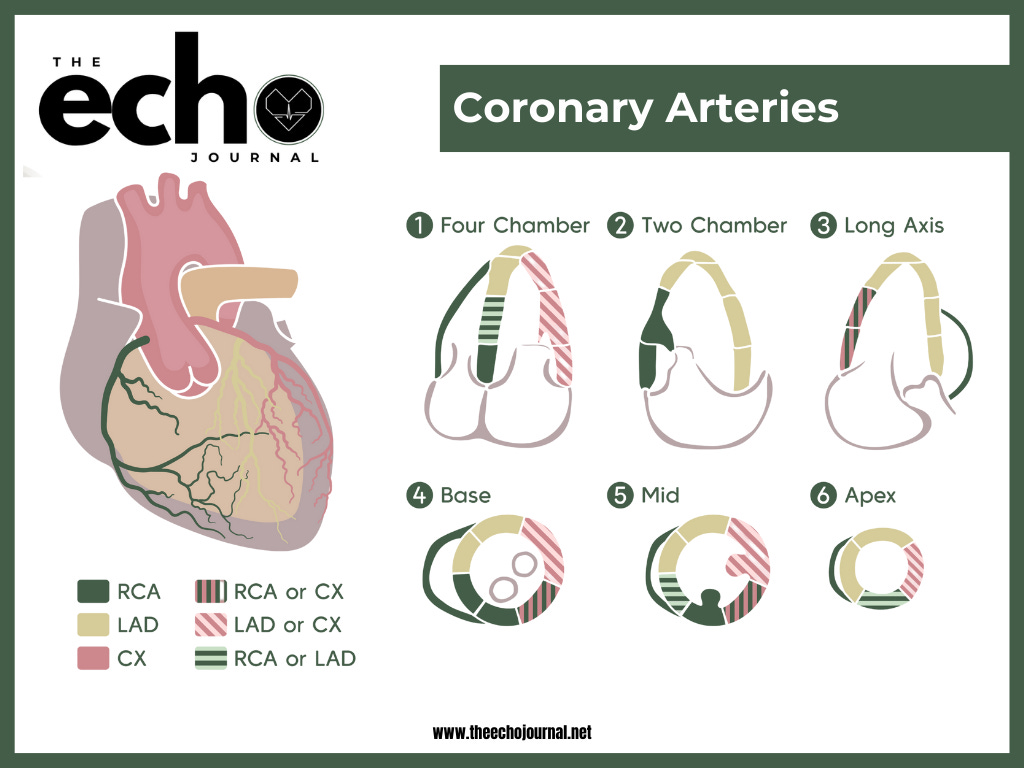

The left anterior descending (LAD) artery—often called the “widow maker”—supplies the true apex, yet the apical cap in the short-axis view is frequently overlooked, allowing critical ischemic findings to go undetected.

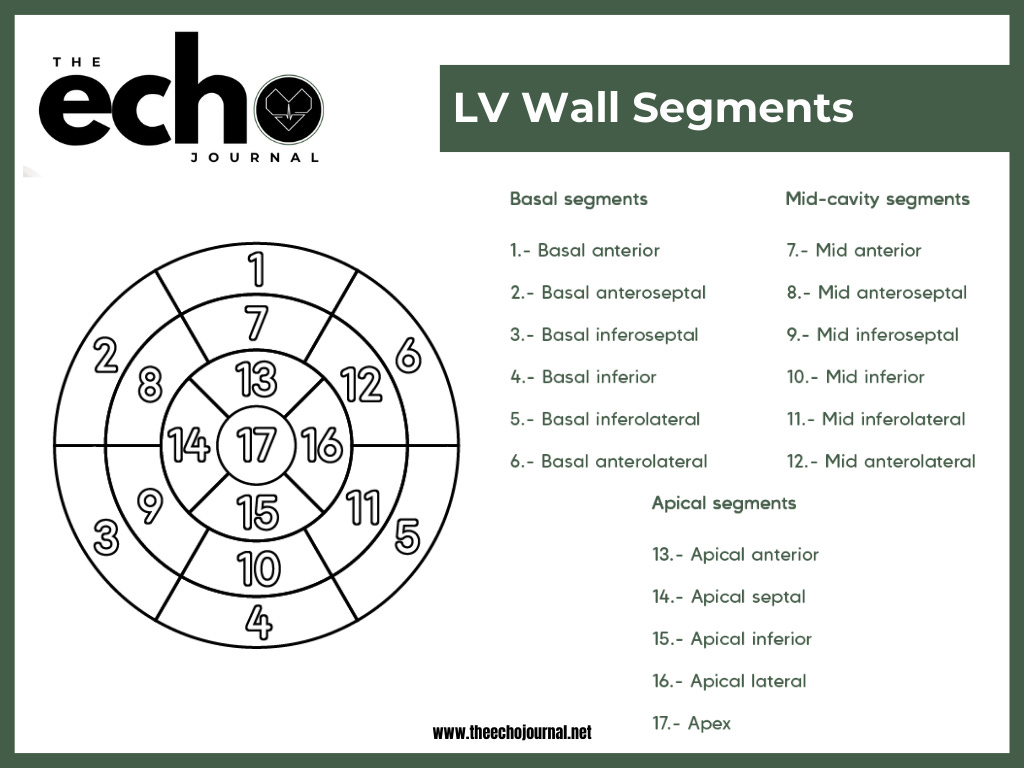

The 17-Segment Model: Why It Matters

The ASE 17-segment model divides the left ventricle into standardized regions that are used across echocardiography, nuclear imaging, cardiac CT, and cardiac MRI. This shared framework allows meaningful communication between imaging modalities and clinical teams.

Applying the segmental model:

Standardizes wall motion reporting

Minimizes vague or subjective descriptions

Facilitates correlation with other imaging and diagnostic tests

General statements like “the anterior wall looks abnormal” lack precision compared with identifying the apical anterior segment as akinetic.

Coronary Artery Territories and Wall Motion

Coronary arteries deliver oxygenated blood to specific left ventricular segments that can be assessed on transthoracic echocardiography. In the most common coronary dominance pattern:

Left anterior descending (LAD) artery: supplies the anterior wall, anterior septum, and apex

Right coronary artery (RCA): typically supplies the inferior wall and basal inferoseptum

Left circumflex (LCx) artery: commonly supplies the lateral wall

Important Considerations

Coronary anatomy is highly variable between patients.

Coronary dominance may be right-dominant, left-dominant, or codominant.

Arterial territories overlap, limiting precise localization based on wall motion alone.

Collateral circulation may preserve regional contractility despite significant coronary stenosis.

Clinical implication:

Normal wall motion does not exclude ischemia, and abnormal wall motion does not reliably localize a specific coronary lesion. A patient may have a severe (e.g., 90%) left anterior descending artery occlusion yet still demonstrate a normal ejection fraction and preserved wall motion on resting echocardiography.

Ischemic vs Non-Ischemic Patterns

One of the most important skills in wall motion assessment is determining whether an abnormality follows a coronary artery pattern or suggests an alternative cause. While ischemic heart disease is common, not every wall motion abnormality is due to a coronary occlusion—often, the overall pattern provides the answer.

Ischemic Wall Motion Patterns

Ischemic regional wall motion abnormalities occur when myocardial blood flow is reduced, with the subendocardium affected first, making early changes subtle.

These abnormalities typically:

Follow the territory of a coronary artery

Involve neighboring segments supplied by the same vessel

Manifest as hypokinesis, akinesis, or dyskinesis

Remember, echocardiography demonstrates how the myocardium responds to ischemia, not the exact location of the coronary obstruction.

Non-Ischemic Wall Motion Patterns

Non-ischemic wall motion abnormalities tend to look different.

In clinical practice, non-ischemic patterns often:

Cross multiple coronary territories

Involve several walls or the entire ventricle

Do not conform to a single coronary artery distribution

These findings are commonly seen in non-coronary conditions, including:

Dilated cardiomyopathy

Conduction abnormalities such as left bundle branch block

Post-cardiac surgery or post-procedural states

Myocarditis or other inflammatory conditions

Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is a classic example of a non-ischemic pattern that can mimic ischemia. On echocardiography, it often presents with reduced motion in the apical or mid-ventricular segments and preserved or hyperdynamic basal contraction. Because this pattern spans multiple coronary territories, it should raise suspicion for a non-ischemic process rather than focal coronary obstruction.

When wall motion abnormalities fail to align with coronary anatomy, it is important to pause and consider these non-ischemic causes before labeling the findings as ischemic. Recognizing these patterns helps prevent misclassification and supports more accurate clinical interpretation.

When evaluating wall motion, looking at the pattern across segments is often more helpful than focusing on a single abnormal segment.

Practical Assessment & Reporting Tips

Accurate wall motion assessment depends on systematic image acquisition and review. Abnormalities should always be confirmed in multiple views and planes, rather than a single window or cardiac cycle.

Key habits that improve accuracy include:

Confirm suspected abnormalities in more than one view

Avoid apical foreshortening, which can falsely suggest dysfunction

Prioritize endocardial thickening over motion alone

Early ischemia may present as reduced thickening before obvious motion abnormalities. When endocardial borders are suboptimal, contrast enhancement can significantly improve confidence in segmental assessment.

When reporting, think in segments—not views. Consistent use of the 17-segment model leads to clearer reports, better communication with the care team, and easier correlation with other imaging modalities.

Developing a strong clinical eye for wall motion takes time, repetition, and deliberate pattern recognition, but it remains one of the most impactful skills a cardiac sonographer can master.

Did you find this helpful?

This article is unlocked and free for everyone—feel free to share it with your network and tag The Echo Journal.

Visit www.theechojournal.net for adult echocardiography board exam tools and practical resources to help you master the art of echocardiography.